“You just can’t understand anything you can’t get your hands on, anything you can’t feel or see or, or count…”

― William Gaddis, J R

Beneath the metropolis’s disorienting system of unimaginable calculability, its economic drive of unique exactness, lays its driving machine, the rapid transportation system, the subway. This mode of transportation becomes a manifestation of the metropolitan necessity for intensity and objectivity, an aversion to the emotional uncertainty of human subjectivity. Thus the blasé disposition becomes formed through the various overwhelming external stimuli of the metropolis, the subway being one of them. This essay will argue that the design and process of the subway and its station assume the metropolitan objectivity that reinforces blasé attitudes.

First, the connection must be made between the subway as a medium to reinforce blasé attitudes in metropolitan life. Blasé attitudes, as defined by Simmel in The Metropolis and Mental Life, is the response to the “rapidly changing and closely compressed contrasting stimulations of the nerves” resulting from the metropolitan style of living, creating an apathetic and indifferent attitude to conceal one’s subjective spirit from the domineering objective spirit of the metropolis (Simmel, 178). The form in which the metropolitan transit system takes resembles a manifestation of the objective spirit of the metropolis, a calculating and rapid system more impartial to the indeterminate emotions of the individual. Thus, the discrepancy between the individual and the metropolis is born, resulting in the necessity of a blasé attitude to defend one’s subjective self against the money-making tempo of the metropolis, a sort of buffer.

With this rapidity involved in everyday metropolises, the subway must operate on the level of procession concurrent with the market, otherwise, bereft of punctuality, the structure of such a system would fall apart. This is why disruptions to the timetable of subways, a timetable of organized consistency with respect to the metropolitan economic system, become near existential, a threat to the blasé attitudes calculability and indifference. These disruptions resemble the “heart” rather than “mind,” as they reflect an emotional turbulence disavowed in the metropolises mode of objective prediction.

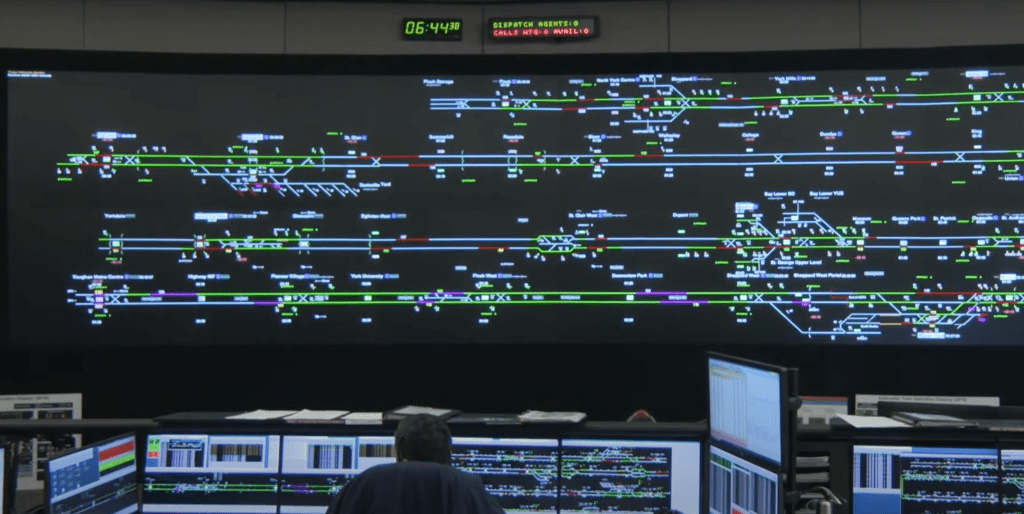

The blasé attitudes resemblance to the metropolises’ calculable structure stems from the form in which subway transportation takes. The momentary lapses in time where the subway is in between stops become zones of indeterminacy, zones lacking orientation amongst chaos where reality is disconnected, only to be rectified once the subway arrives at said stop, resuming the normality of calculus and determinancy. The disconnect and sudden reconnect reflect the 0 and 1’s of a computer language, where during the lapse of time in between stops, or the 0, the individual is led into a psychic state of purgatorial waiting, waiting for the moment their function as an economic unit can be fulfilled by being granted exit at a stop, or the 1. And so, through the calculus of automation mixed with transportation, the individual becomes increasingly more blasé in a feedback loop where the objectivity of the metropolis is manifested in the transportation the individual takes.

In examining the blasé attitude further, the disposition must be surveyed in the subway station itself. The subway station operates as the symbolic recognition of an arrow of time, a temporally linear structure of time where the future is held in prediction. Thus, the reality of the subway station discloses an incompatibility with loitering, a rejection of discontinuity with which the architecture asks. As a result, the individual is placed in a codified conjunction with the station itself, recognizing the blaséness of the station itself, its objective of flow disregarding human connection. The individual then does not seek interaction with others as the station prompts movement regardless of human emotion, and so, the blasé attitude is intensified. This is proved further by the presence of busking, which subverts the regularity and predictability of the station. The station thus becomes a separate function, a breaking of the temporal flow which it held in conformity to the money-economy it so reflects, where music dispels the objective for the emotional, irrational, and the abstract. Through this, the station, as opposed to its non-busking form as an objective linear arrow of time, becomes a harmonious congregation of recognition of subjectivity, a moment of true individuality.